The Nobel citation for Professor Smith reads as follows:

The Nobel citation for Professor Smith reads as follows:"for having established laboratory experiments as a tool in empirical economic analysis, especially in the study of alternative market mechanisms"

Having being fascinated by experimental economics for a long time, I finally mustered enough courage to conduct a small experiment in my class yesterday. My main motivation (aside from my own curiosity) was to expose my students to experimental economics. I attempted to replicate a trading game described in detail by Professor Charles Holt.** The game simulates a trading process in a pit market. In the experiment, each buyer or seller is given a poker card randomly. Buyers are given cards with either the diamond or heart (RED) symbol while sellers are given cards with the spade or club symbol (BLACK). The number printed on a buyer's card represents his/her valuation of a hypothetical good to be purchased. The number on the seller's card represents the seller's cost. Buyers are not permitted to pay more than their valuation of the goods while sellers are not permitted to sell at prices below their cost levels.

Forty students participated in the experiment. Due to time constraint, we only had time to conduct eight rounds of trading. Students assume the same role (seller or buyer) throughout the first seven rounds. In the eighth round the roles were reversed.

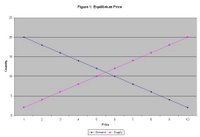

Forty students participated in the experiment. Due to time constraint, we only had time to conduct eight rounds of trading. Students assume the same role (seller or buyer) throughout the first seven rounds. In the eighth round the roles were reversed.The results from the experiment were stunning. Our theoretical prediction for the equilibrium price is RM5.50 (Figure 1).

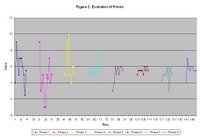

The transaction prices were fairly dispersed at the beginning of the trading rounds. However, by the sixth round of trading most of the transaction prices had converged to RM5.50 (Figure 2).

The transaction prices were fairly dispersed at the beginning of the trading rounds. However, by the sixth round of trading most of the transaction prices had converged to RM5.50 (Figure 2).The experience of conducting this little experiment is certainly one of the most exciting moment in my teaching career. Judging from the animated haggling by the students during the experiment, I am sure many of them found this experience to be a fun way to learn economics or experimental economics.

I will certainly look for opportunities to conduct more experiments in my future lectures!

* Chamberlin, Edward. (1948). "An Experimental Imperfect Market", Journal of Political Economy, Vol.56, pp.95-108.

**Holt, Charles. (1996). "Classroom Games: Trading in a Pit Market", Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol.10, No.1, pp.193-203.